The 23rd Study of Design Fundamentals Seminar: The Birth of Professional Designers in East Asia: A Case Study of Chen Zhifo's Study at the Tokyo Art School

Dec 14th, 2021

Kyushu University Faculty of Design explores the fundamental methodology of design for integrating a wide range of designs. For the 23rd online seminar, titled “The Birth of Professional Designers in East Asia: A Case Study of Chen Zhifo’s Study at the Tokyo Art School”, We are pleased to invite Dr. Zhang Jing, who specializes in the history of design and product design at the China Academy of Art. Chen Ash, a member of the Center for Design Fundamentals Research, Kyushu University, summarizes and reflects on the event.

The first thing I noticed in this lecture was the use of the term “professional designer.” According to Dr. Zhang, professional designers emerged later than design in modern East Asia because in modern Japan and China, for a long time, artists and literary scholars were involved in bookbinding and stage design, and their work was situated between art and design. Furthermore, Dr. Zhang believes that there are several forms of work for professional designers at present, including in-house designing, setting up one’s own design office, and freelance designing. In fact, the various forms of professional designer work did not emerge simultaneously in modern East Asia; rather, they grew gradually according to the needs of social and market development.

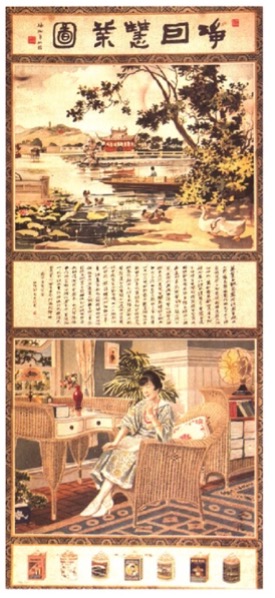

Advertisement painted by Xu Yongqing and Zheng Mando, 1920s (The Old Moon Sign(《老月份牌》), 1997, Shanghai Pictorial Press, p. 29)

In this case, Chen Zhifo (1896–1962) represents the earliest generation of professional designers in modern China. After majoring in textiles at an academy in Hangzhou, Chen continued as a teacher at the same academy until 1918; following which, he became the first Chinese design student to travel to Japan to study pattern design at the Tokyo Art School. After graduating in 1923, he returned to China and pursued design work and design education. Then, he established Shang Mei Design Studio in Shanghai and collaborated with publishing institutions such as the Commercial Press, Tian Ma Bookstore, and Kai Ming Bookstore on bookbinding. Chen Zhifo was also involved in training artists at various acclaimed institutions in China and served as the principal of the interim National School of Art, after the merger of two art universities, which were the forerunners of the present Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. However, from 1937 onward, he gradually moved away from design work to focus on traditional Chinese bird-and-flower painting.

To understand the genesis of modern professional designers such as Chen, and the development of modern design in East Asia, it is important to know the historical context of that time. From a cultural-historical perspective, the late 19th and early 20th centuries were an important period in Chinese history, called the second “西学东渐(westernization).” During these decades, China imported Western liberal ideals (e.g., democracy and science) and technologies from the West and Japan, and the process of change, from the feudal ruling class to the intellectuals, started with China constantly searching for a direction to shape the country’s destiny. Specifically, the active introduction of the advantages of Western civilization from Japan, which it had already absorbed and understood, was a major shift in the tradition of cultural exchange between China and Japan. This change began after the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). The reality of defeat forced the Qing Dynasty to realize the impact of Japan’s modernization through the Meiji Restoration. In addition, owing to the convenience of the Chinese character, culture, and geographical proximity, China imported modern civilization through Japan, and this trend encouraged many young people, such as Chen, to study in Japan.

However, most Chinese students who went to Japan at the time were motivated to study economics, law, medicine, military, and other professional courses, whereas relatively few studied art, while no one had studied design prior to Chen. This reflects the peculiarity of Chen’s study at the Tokyo Art School, where the concept of modernity was systematically imported into China through youth studying overseas and based on their work after returning to China. In other words, modern design in China adopted the path of gaining knowledge and experience from abroad.

Thus, Dr. Zhang sees the emergence of professional designers, such as Chen, in modern China, as an inevitable result of the trend of “西学东渐(westernization).” Hence, these professional designers had a clear understanding of design that is different from the traditional concept of craftsmanship and transited to working in a way that is adapted to the manufacturing processes and procedures of the industrial age, which is similar to professional designers’ current working style.

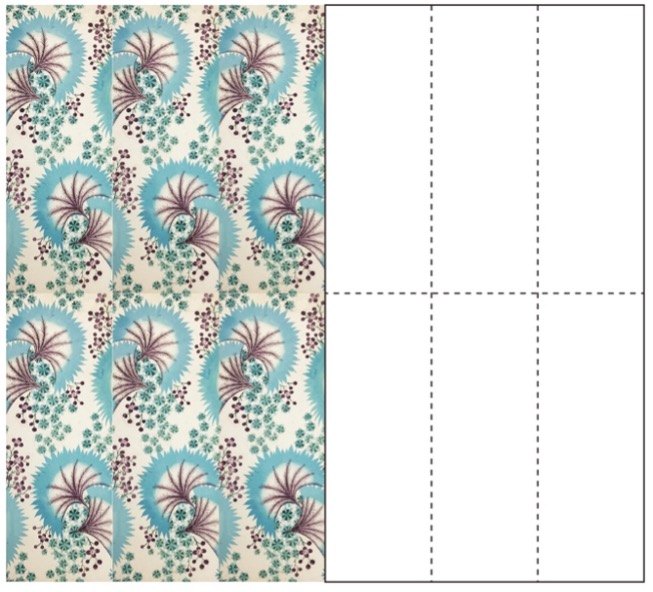

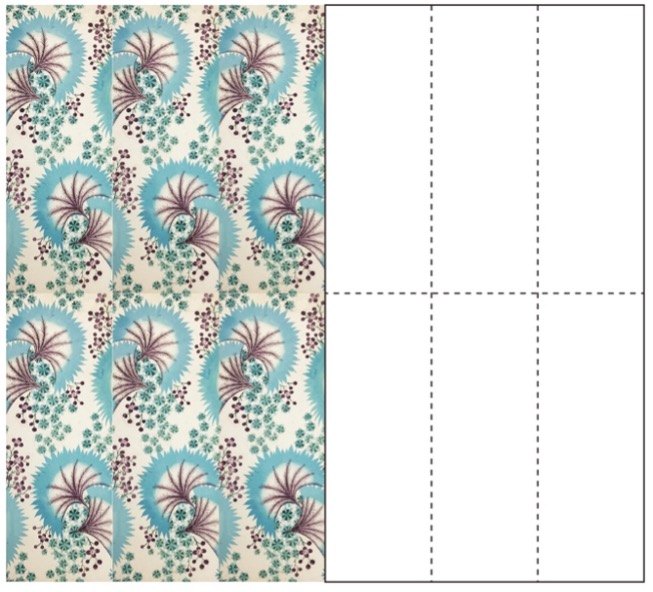

Textile (dyeing and weaving) patterns designed by Chen Zhifo, Fine Art of Chen Zhifo’s Patterns(陈之佛图案精品 ), Cixi City Federation of Literary and Art Circles, Chen Zhifo Art Museum, 2016, p. 11.

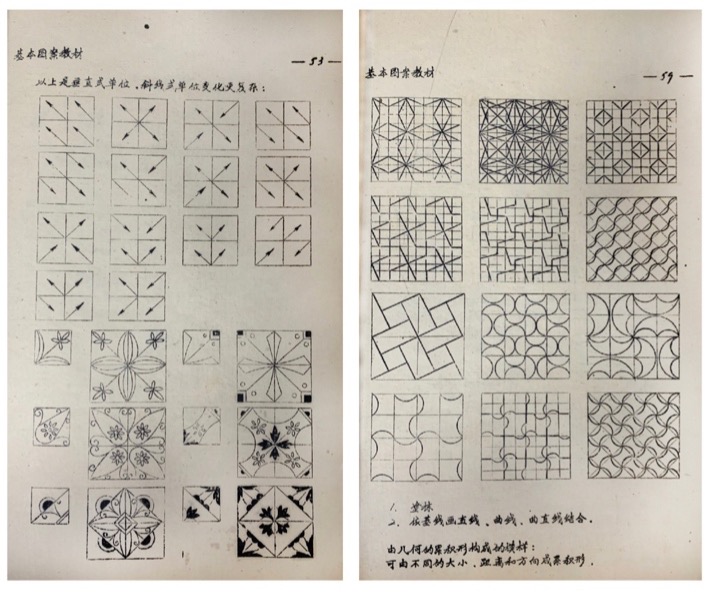

Transcript of the Lectures on Chen Zhifo’s Patterns (陈之佛图案讲稿), Collection of China Academy of Art

Dr. Zhang argued that professional designers in China in the early 20th century were keen to reform society through cultural and intellectual transformation, given the historical background and social environment prevailing during that period. They were “born” with a strong sense of national identity and social responsibility, and therefore shared a close relationship with the social, cultural, and ideological activities and were tasked with esthetically realizing China’s cultural and intellectual revolution.

Dr. Zhang’s narrative shows that professional designers, such as Chen, faced a complex contradiction during that time. As a result of the alternation of the traditional Eastern culture to the new Western education system, professional designers had the dual cultural attributes of the East and West, a traditional and modern outlook, that made them deal with cultural interdependence and conflicts that arose concurrently. They experienced the pain of war and an intense cultural shock as they had to leave their homeland, in search of new knowledge, but tried to tear a hole in the Western ideals they had learned, to place their own nostalgia in it; they studied design that was created in the West but were eager to spread the traditional esthetics and ideas of East Asia to the world through design.

At the end of his lecture, Dr. Zhang discussed the reasons for Chen Zhifo’s gradual drift away from design work after 1937. Owing to The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and the following market downturn, Chen, who had initially returned to China with the intention of modernization, eventually felt uneasy about working as a professional designer in China and returned to traditional Chinese art.

These results seem to reflect the following words from an ancient Chinese work, called Yanzi chunqiu(《晏子春秋・雑下之十》). “The oranges to the south of the Huai River are large and sweet; however, when cultivated north of the river, they become shrunken and bitter, the same with its leaves, and the taste of the fruit having changed in its entirety.” Before the concept of design was introduced to the East, it had already emerged, grown, and blossomed in the West, and was closely connected to the environment in which it existed, adapting and changing the environment in its own unique way. Moreover, when the fruits of design entered China as an imported product, especially after the region had been developing its own relatively stable system for thousands of years, the experience of vehemence, pain, and aberrations that occur seems inevitable.

During that period, the proportion of agricultural population as a share of the total population and agricultural output to total industrial and agricultural output had both reached 80–90%. Therefore, the term “design” became almost synonymous with the elite class, who had the “privilege” to interpret, communicate, and consume it. It seems difficult to imagine that such pioneering, well-designed books and magazines, glamorous costumes, and ostentatious stage settings would echo in the vast mountains, fields, and valleys of China. As a result, the development of design at that time was fragile and almost in oblivion. When war, poverty, and other drastic changes related to survival and life emerged, design, along with the beautiful fabrics and propaganda posters it produced, would be swept away in the dust and abandoned in the corners of life.

Even today, it is difficult to declare that this fragility of suspended design has disappeared, or that interpretations of design, beauty, and good living are no longer the preserve of the elite. Most of the definitions, interpretations, and evaluations of design remain in an academy or on the white walls in a spotlight. Perhaps we still find it difficult to believe that we have escaped the dilemmas, contradictions, and predicaments faced by professional designers in modern East Asia.

Date

Dec 14th (Tue), 2021: 17:30-19:30

Venue

Online

Contact

Design Fundamental Seminar

designfundamentalseminar@gmail.com

-

23rdSeminerPoster

閉じる

23rdSeminerPoster

閉じる

23rdSeminerPoster

![九州大学イノベーションデザインネクスト[KID NEXT]](https://www.kidnext.design.kyushu-u.ac.jp/wp-content/themes/kidnext/img/logo_header.png)